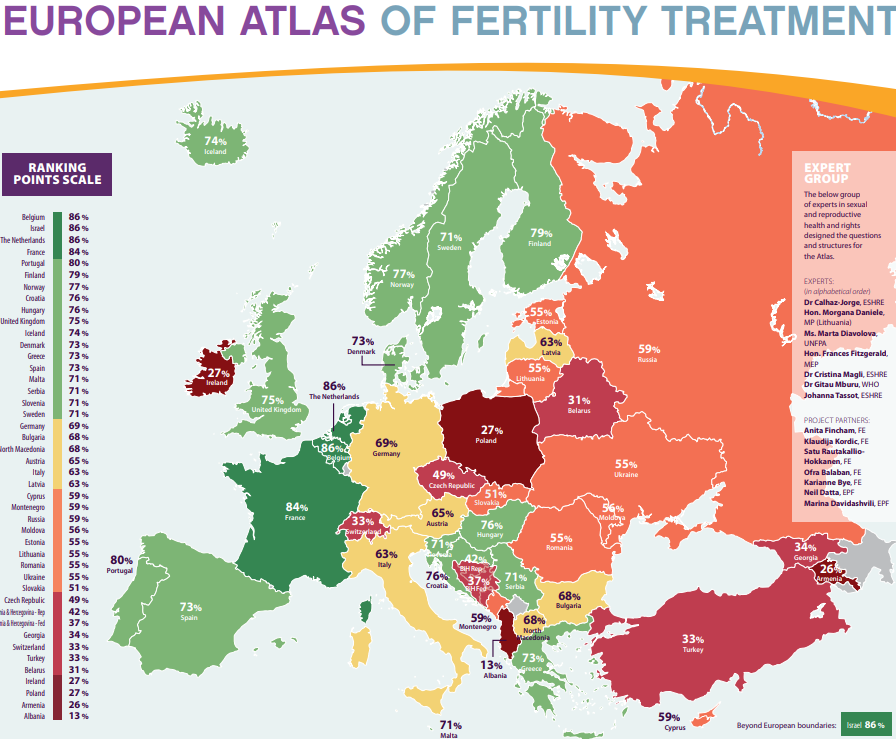

European Atlas of Fertility Treatment Policies

23 definitions

- Invisible Cage , Predictive Policing

- Thucydides’ Trap

- Marine Heatwaves , Mass Mortality Events

- Global Gateway , Brussels Effect , Human-centric Digital Economy

- Value-based foreign policy , Club governance

- Austria’s New Whistleblower Act

- Fractional Orbital Bombardment System

- Socially Distanced Diplomacy

- Cyber-authoritarianism

- Regional Clean Hydrogen Hubs

- Bridging-based Ranking

- Biodiversity Finance

- Nature-positive Financial Sector

- Net-Zero Political Economy

- Hopeium

- Paris Club

- Agile Governance

- BiodiverCities